Introduction

Passkeys now protects billions of accounts, redefining how the world signs in through stronger, more secure authentication without a password. Yet this global movement runs deeper than most realize. While passkeys implements thoroughly scrutinized standards developed by the FIDO Alliance in collaboration with the W3C, global adoption, however, is driven by a central layer that extends beyond the open standards, one that remains little-researched, varies by implementation, and it is often misunderstood.

Although the technology has existed for years, the breakthrough that brought passkeys to everyday users at scale was not just stronger security but simplicity. The ability to access and sync passkeys across devices through credential managers such as Apple Passwords and Google Password Manager fulfilled a bold vision: “Synced passkeys are made for planet-scale adoption with billions of users.” This innovation delivered the usability needed to turn the FIDO Alliance’s objective to “help reduce the world’s over-reliance on passwords” into reality.

Although the protocols extended to enable synchronization, they do not define how passkeys should be synced or protected. This lack of specification leaves the proper security of a passkey dependent on each provider’s design and implementation. Among the most widely used ecosystems, we found a distinct design within Google’s infrastructure: the Cloud Authenticator, operating behind the scenes to provide billions of users with a secure, seamless passkey experience.

While passkeys, even when synced, have raised the bar and eliminated many traditional attacks, attackers continue to adapt and find new ways to exploit emerging systems. Our research into real-world implementations uncovered weaknesses that expose new attack vectors. These findings inspired this series, which explores the hidden architecture powering the world’s move to passwordless authentication.

In this series of blogs, we will pull back the curtain and explore the passkey revolution in three parts:

- In Part 1: Global breakthrough, we’ll explain passkeys in plain terms, why they protect today’s most common attacks, and reveal the innovation behind global adoption.

- Part 2: Google Cloud Authenticator, we’ll uncover the hidden mechanisms behind synced passkeys and their implementation within the Google ecosystem.

- Part 3: Evolving threat landscape, we’ll examine new attack vectors emerging in a passwordless environment and the potential risks that will define future cybersecurity challenges.

This article is based solely on publicly available information, open-source code (including Chromium), and observable system behavior. The research detailed here was performed for responsible and ethical security analysis.

Passkeys in a nutshell

A passkey is a passwordless cryptographic credential built upon the FIDO standards, specifically the WebAuthn and CTAP protocols. Unlike traditional multi-factor authentication, which relies on shared secrets such as passwords or one-time codes that attackers can phish, leak, or replay, passkeys eliminate these weaknesses by design. Much like SSH transformed secure internet communication, passkeys apply the same principle of asymmetric cryptography to provide secure authentication. During registration with an online service, the client generates a unique key pair. The private key is securely stored on the client’s device, while the public key is sent to the service for future authentication. During authentication, the client proves ownership of the private key by signing a challenge provided by the service.

The authenticator: The heart of passkeys

A trusted component called the authenticator manages the cryptographic operations and verifies the user. The authenticator:

- Generates the key pair during registration and keeps the private key securely protected.

- Produces a statement proving that the public key shared with the service was generated in a secure and trusted environment. (AKA attestation).

- Controls access to cryptographic actions using one or more authentication factors:

- Something you are (biometrics)

- Something you know (PIN or unlock pattern)

- Something you have (a trusted device, user interaction, or proximity)

- It creates an assertion by signing the challenge and the security properties, such as whether the user was verified. This gives a requested service assurance that the response originates from a verified user on a trusted device.

Authenticators can take different forms. Some are built into the user’s device, while others are portable hardware devices:

- Platform authenticators reside inside your device. They isolate and protect the cryptographic operations, typically by a hardware chip like a Trusted Platform Module (TPM), Secure Enclave (SE), or Trusted Execution Environment (TEE). The authenticator can control access using local platform user verification (biometrics or a PIN, e.g., Windows Hello, Touch ID, or Face ID).

- Roaming authenticators are portable devices that can be connected to multiple client devices while keeping the private key locked within the portable hardware. The most common examples are hardware security keys like YubiKey or Feitian keys. This authenticator type connects over USB, NFC, or BLE.

Having outlined the role of the authenticator, let’s see the basic flows of how FIDO registration and authentication work.

Basic registration—creating a passkey:

When a user visits a website or app that supports passkeys and starts to register with a service (relying party):

- The service requests the creation of credentials.

- The authenticator verifies the user with features like biometric or knowledge factor.

- The authenticator generates a unique cryptographic key pair.

- The public key is sent to the service and stored there, while the private key is kept secure on the authenticator.

Figure 1. Basic registration flow.

Every time a user registers with a new relying party, the authenticator stores a new private key tied to that relying party’s domain (the RP ID) while the relying party stores the public key tied to the newly registered user on its server.

Basic authentication—log in with passkey:

When a user comes back to log in:

- The service (relying party) sends a random challenge (at least 16 bytes in length).

- The authenticator verifies the user with features like biometric or knowledge factor.

- The authenticator retrieves the private key matched to the relying party ID and uses it to sign the challenge.

- The signed challenge is sent back to the service.

The service validates users’ credentials without exposing symmetric secrets such as passwords or one-time codes. It relies on the stored public key to verify the signature, while the private key always stays securely on the user’s device.

Figure 2. Basic authentication flow.

From a user experience perspective, passkeys make two-factor authentication feel effortless by combining everything into a single step. You simply unlock your phone or computer while, in the background, the authenticator proves that a verified user possesses the private key bound to the visited relying party. This delivers a login experience that is both safer and more practical than traditional MFA.

Why passkeys hold up better security

For decades, passwords and other symmetric secrets such as tokens and one-time codes have been the weakest link in digital security. They can be stolen, guessed, reused, or phished, and once exposed, they can be exploited repeatedly. Entire breaches and underground markets thrive on stolen credentials, fueling a constant cycle of account takeovers and identity theft. Passkeys are not only more practical, they are designed to eliminate entire classes of attacks that passwords and traditional MFA could never fully resist. Here, we describe how passkeys eradicate the threat of three common attack methods.

Replay attacks

A replay attack occurs when an attacker intercepts a valid authentication artifact, such as a password, hash, or token, and replays it to gain unauthorized access. Passkeys prevent this by design, turning every authentication into a single-use event. The relying party issues a fresh random challenge for each authentication session, and the client signs that challenge with the private key. Because the signature is valid only for that specific challenge, a captured signed response cannot be reused to authenticate later.

Phishing

Passwords and OTPs are vulnerable to phishing because attackers can trick you into typing them on a fake website. A passkey, however, can only be used on the specific domain it was created for. During login, the browser verifies that the origin of the page the user is visiting matches the relying party ID associated with the stored credential. This origin check makes passkeys inherently resistant to phishing, since even a convincing look-alike site (like G0og1e.com) cannot trick the authenticator into releasing a valid credential.

Man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks

If attackers listen to the authentication connection, they only see non sensitive information. During registration, the authenticator shares a public key, from which it is computationally infeasible to derive the private key. During login, the authenticator signs a fresh, session-bound challenge that the relying party verifies with the stored public key. Neither the public key nor the signed challenge can be used to impersonate the user or reveal sensitive information.

The adoption hurdle: Isolation vs. sync

The very property that makes passkeys secure has also been their most significant barrier to adoption for many years. While on paper it seems to be a perfect solution, offering smoother logins and stronger security, a key limitation prevented their widespread use.

Early passkey implementations were designed so private keys were unexportable and bound to a single device. These keys are typically protected by hardware such as a Trusted Platform Module (TPM), which prevents them from being copied or extracted and provides cryptographic proof (attestation) that the private key was created and owned only by that specific device. The unexportability protects keys from theft and establishes trust in the user’s device, but it also creates a limitation: authentication is possible only with a particular device. If the device is lost or replaced, the private key and the ability to log in are lost, too.

FIDO’s first breakthrough to address the single-device limitation came in 2020 with the introduction of Cross-Device Authentication (CDA). This innovation enabled a smartphone to serve as a secure authenticator for nearby devices, extending a user’s trusted authentication factor to their other hardware. While this was a significant step forward in usability, it failed to solve the critical issue of recovering from device loss. The reliance on a single, primary authenticator meant a lost phone still resulted in a painful recovery process.

To enable global adoption, FIDO extended the WebAuthn framework to allow private keys to be exportable and unbound to a single device. This change allows users to create a passkey on one device and have it synced and available across others. It also enables cloud-based recovery, allowing users to restore access even if all their devices are lost. Because password managers are already widely used to synchronize user secrets across devices and provide recovery services, extending them to support passkey secrets was a natural step. However, making private keys exportable and accessible across devices introduced new security challenges. The WebAuthn standard does not specify how these keys should be protected from unauthorized access across multiple nodes, including creation, synchronization, and recovery. This gap leaves the actual protection of private keys dependent on each credential provider’s implementation. Early proposals to strengthen the synced key protection, including the devicePubKey and supplementalPubKeys extensions, were explored but later dropped from the protocol.

Secure synced approaches

Can we preserve the security guarantees of unexportable keys while enabling recovery and sync across devices?

Several strategies have been explored in recent years, three concrete models are already in use today. They all share a core idea: encrypt the passkey’s private keys so they can be stored safely on external infrastructure. A single symmetric key encrypts all of the user’s passkeys before they are backed up or synced. For simplicity (though terminology may vary across implementations), in this blog, we’ll refer to this master key using Google’s term: the Security Domain Secret (SDS).

From this core concept, three practical models for secure synchronization/backup have emerged:

- Distributed trust: split the SDS into shares and distribute them across trusted parties. Only a quorum (a minimum number of parties working together) can reassemble it.

- Trusted bootstrap: protects the SDS with a bootstrap passkey through an external authenticator.

- Cloud authenticator: The cryptographic operations are shifted into a secure enclave within the cloud.

1. Distributed trust

Imagine a vault that can only be opened with three different keys. You hand each key to a different relative. No person can unlock it independently, but the vault opens when enough of them come together. That is the principle behind Distributed Trust.

The user creates a randomly generated Security Domain Secret (SDS) to decrypt and encrypt the passkey. This SDS is divided into multiple shares using Shamir’s Secret Sharing (SSS), a cryptographic algorithm that splits a secret into several unique pieces. Each share by itself reveals nothing about the original secret, but when a sufficient number of shares are combined, the SDS can be reconstructed. Once recovered, the SDS allows a new device to decrypt the encrypted passkey blob and restore access.

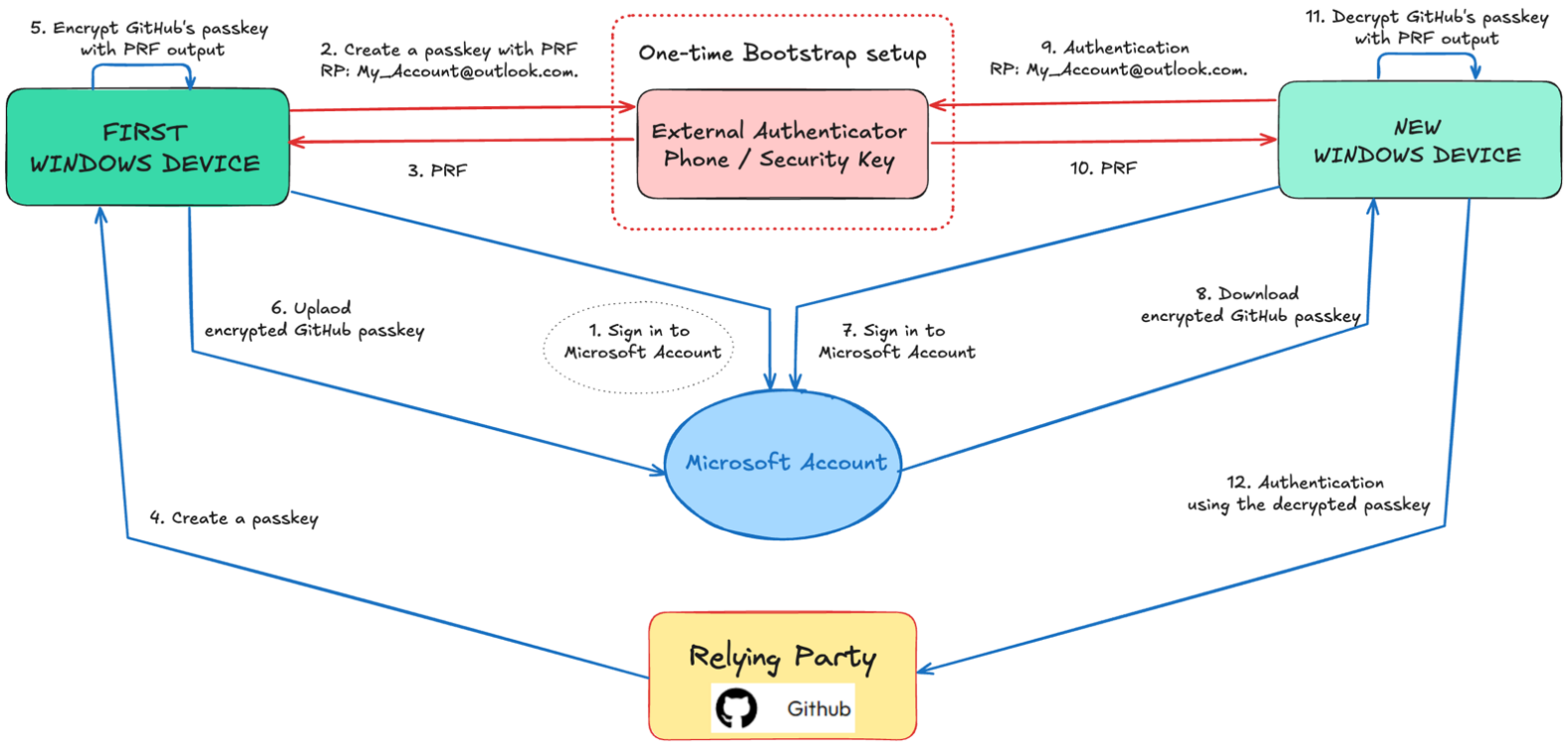

2. Trusted bootstrap (Microsoft’s approach, available in preview to Windows Insiders at the time of writing)

Imagine a vault that can only be opened by unlocking another vault you already own. The first vault contains the special key needed to open the second one, and without access to that first vault, the second will never open. This is the idea behind Microsoft’s synced passkeys. On the first Windows device, a one-time bootstrap setup is performed. During this process, the device creates a special bootstrap passkey in an external authenticator such as a phone (via QR scan) or a hardware security key. In this case, the Windows account acts as the service (relying party) with an RP ID in the form of <user account>@outlook.com.

The bootstrap passkey uses the WebAuthn Pseudo-Random Function (PRF) extension to enable Windows Hello to derive the Security Domain Secret (SDS) securely. When the user later adds a new Windows device, after logging in to their Windows account, they authenticate with the same external authenticator, requesting the same bootstrap passkey, enabling Windows Hello to derive the exact same SDS securely within the new device.

Once this bootstrap step is complete, Windows Hello takes over and protects the SDS locally. From that point on, the SDS encrypts and decrypts the user’s passkeys, which can then be synchronized safely across the Windows account.

Figure 3. Windows secure sync using a bootstrap key.

Each of the two methods has advantages and disadvantages: Distributed trust works well for secure recovery but is challenging to scale, since each user would need trusted parties to keep the shares and authenticate the user before helping restore the SDS on a new device. Trusted Bootstrap can scale more easily but fails to ensure recovery if both the user’s device and the Bootstrap authenticator are lost. Both approaches, however, share the same security limitation:

Backing up a passkey’s secret from one device to another means passkeys are no longer protected by hardware isolation.

Hardware isolation is a critical security property that prevents private keys from being exported even by highly privileged malware. However, these two methods must also depend on software-level protections, which introduces additional risk. An attacker with system-level access could potentially obtain the SDS to decrypt passkeys or grab private keys in unencrypted form. To address these risks, the third approach, Cloud Authenticator, introduces a new design combining strong isolation and seamless synchronization across devices.

3. Cloud authenticator (Google’s approach)

An authenticator has two jobs: verifying the user and performing cryptographic operations—key generation and signing. In the cloud authenticator model, these jobs are split. User verification stays on the device, key generation and signing happen inside a cloud enclave. Here’s how that model works in four steps:

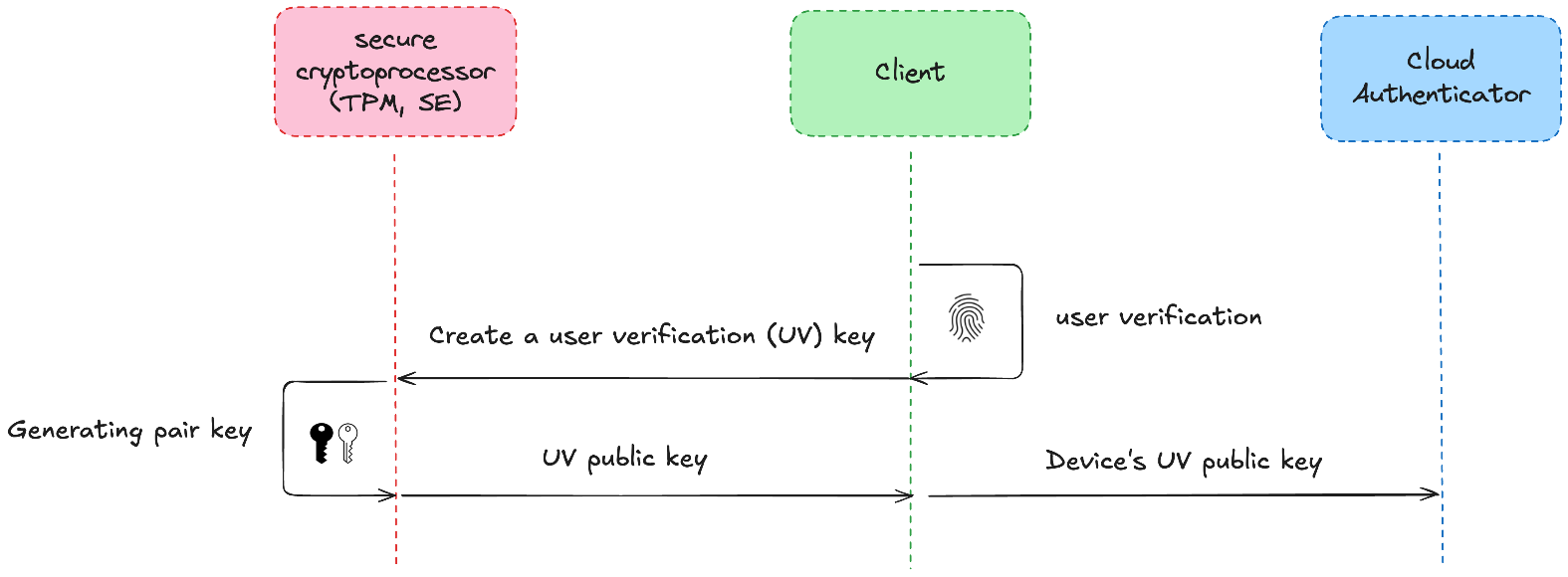

A. Trust anchor on the account’s device using a device-bound key

On every device where the client is connected to a Google account and wants to use the account’s passkey, the client creates a device-bound key pair inside a secure hardware cryptoprocessor (TPM or SE). This private key is saved within hardware; it is non-exportable and gated by local platform user verification, such as biometrics, device PIN code, or unlock pattern. The client uses this hardware device-bound key to sign requests sent to the cloud authenticator, proving that a verified user is present on an authorized device.

Figure 4. Client registers a device-bound public key with a cloud authenticator to prove a user on a trusted device.

B. Security Domain Secret (SDS)

During registration of the first device before the client starts using the first account’s passkeys (Google profile passkeys), the client generates the SDS, a master key for the account’s passkeys. The SDS is designed not to be stored in plaintext. Instead, the cloud authenticator encrypts the SDS:

- For recovery copy: The SDS is encrypted for the cloud recovery key store and can be used only during account recovery after the recovery service validates an account knowledge factor (for example, a lock-screen PIN).

- For verified new account devices: The SDS is encrypted so that only the cloud authenticator can open it when a new device is being registered, after the user verifies with an account’s knowledge factor (for example, a lock-screen PIN).

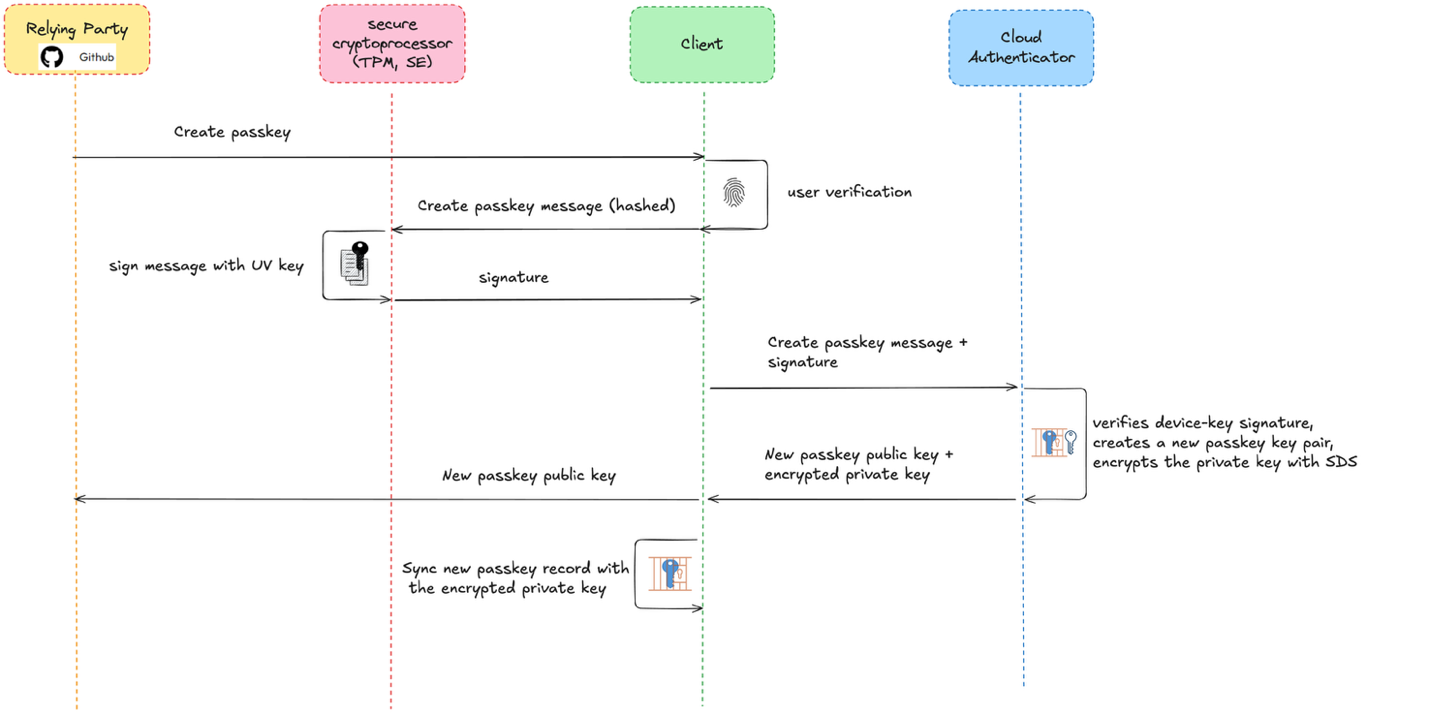

C. Passkey registration

When a user registers with a passkey-enabled website or app, the relying party (RP) asks the browser to create a passkey for the account.

- The user performs a local verification, such as entering a PIN or using biometrics, which authorizes the device to use its hardware key to sign the request

- The client signs a hash of the create message using the device-bound key and sends the message and signature to the cloud authenticator.

- The cloud authenticator:

- Verifies the device-key signature,

- Creates a new passkey key pair tied to the current RP ID

- Encrypts the private key with the SDS

- Returns the public key

- Returns the encrypted passkey record to the client

- The client returns the public key to the RP.

- The client (or the authenticator) syncs the encrypted passkey record across the account’s devices.

Figure 5. Basic registration flow using Cloud Authenticator.

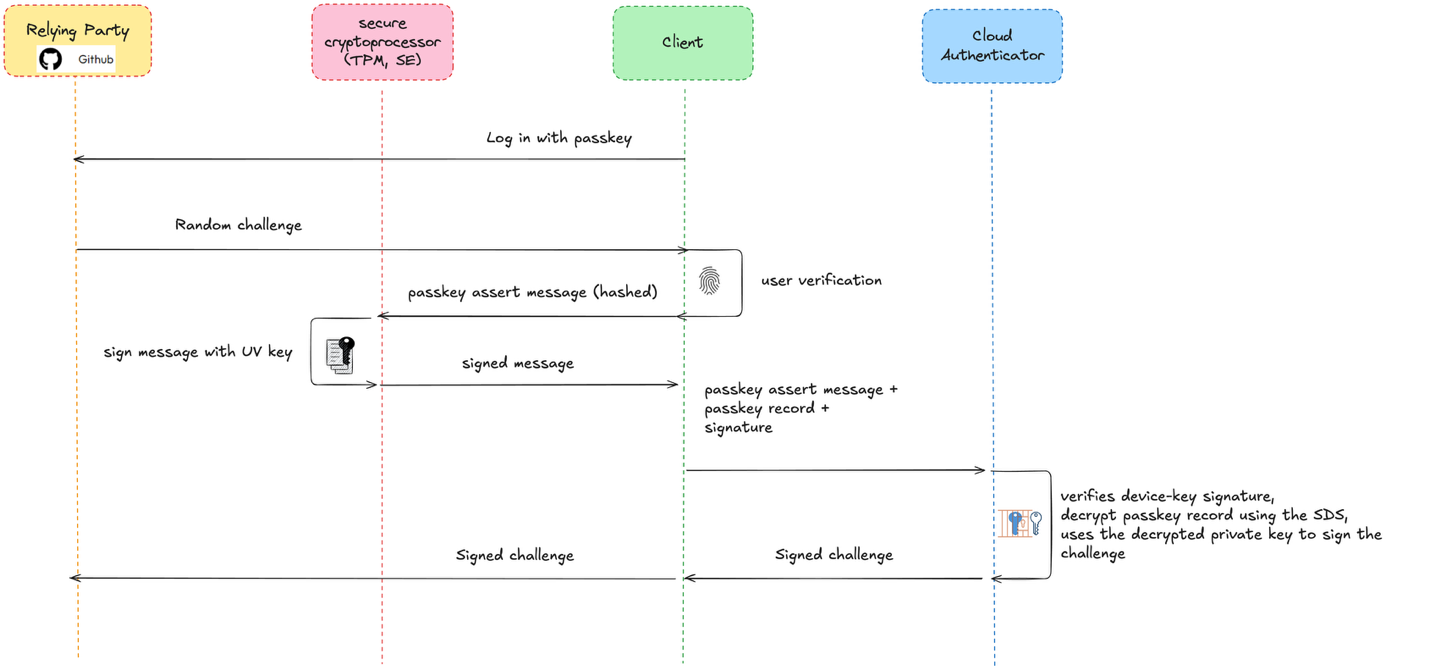

D. Passkey authentication

- The RP sends a random challenge to the client.

- The user performs a local platform gesture (user verification), signs an authentication request with the device-bound key, and sends it along with the relevant encrypted passkey record to the cloud authenticator.

- The cloud authenticator:

- Verifies the device-key signature

- Decrypts the passkey record using the SDS.

- Uses the decrypted private key to sign the challenge

- Returns the signature

- The client forwards the result to the RP, which verifies it with the stored public key.

Figure 6. Basic authentication flow using Cloud Authenticator.

With this design, passkeys’ private keys remain protected inside a secure cloud enclave that performs all passkey cryptographic operations internally, ensuring they don’t leave the isolated environment or become exposed to software on the user’s device. By combining local user verification and device-bound key with cloud-based isolation, Cloud Authenticator solves the core challenge of scaling passkeys globally, keeping hardware-level security impact while enabling seamless synchronization and recovery.

Up next: The Google Cloud Authenticator

Cloud Authenticator represents one of the most widely deployed approaches to bringing passkeys into a world where security and convenience can finally coexist. Yet, while the underlying FIDO and WebAuthn protocols are well defined and extensively evaluated, the cloud-backed authenticator itself is not directly specified in the standards. To better understand the assurance and risk of this model, the upcoming article, Part 2: The Google Cloud Authenticator, examines its design through analysis of Chromium’s open-source implementation and observable runtime behavior. Building on this foundation, the following analysis in Part 3 highlights how security assumptions manifest in practice and how both attackers and defenders may approach a cloud-backed passkey.

Arie Olshtein is a senior malware analyst at CyberArk Labs.