In this blog post, we present our approach for uncovering vulnerabilities by combining LLM reasoning with static analysis. By layering an LLM on top of CodeQL, we significantly reduce the overwhelming noise of false positives that typically buries security teams. The result is a workflow where developers and security researchers can focus only on findings that have genuine potential to be exploited.

This approach led us to create Vulnhalla, a tool that allows only the “true and brave” issues to pass through its gates. Using Vulnhalla, in just two days of work and with a budget of under $80, we identified the following vulnerabilities:

- CVE-2025-38676 (Linux Kernel),

- CVE-2025-0518 (FFmpeg),

- CVE-2025-27151 (Redis),

- CVE-2025-8854 (Bullet3),

- CVE-2025-9136 (RetroArch),

- CVE-2025-9809 (Libretro),

- CVE-2025-9810 (Linenoise).

- … and we continue to find new leads

This article is based solely on publicly available information, open-source data and responsible security research. All vulnerabilities described were disclosed to affected vendors prior to publication.

Challenges of using LLMs for vulnerability hunting

Ever since AI entered our lives, we’ve been wondering whether it could be used to identify security vulnerabilities, as manual vulnerability research is time-consuming and requires a significant amount of in-depth knowledge.

Turns out we weren’t the only ones thinking about that. Google DeepMind, for example, initiated a project called NapTime, which later evolved into Deep Sleep, designed to identify security issues. Not long ago, OpenAI introduced us to Aardvark, an AI agent intended to achieve the same goal. Clearly, there is a demand to automate the cumbersome job of vulnerability research.

In the past, the primary challenge with using large language models (LLMs) for vulnerability detection was the limited context window for a large code base. However, today that’s changing; some models can now handle up to a million tokens.

With today’s LLMs, huge context, it mostly comes down to two problems:

- The WHERE problem

- The WHAT problem

The WHERE problem is that the LLM doesn’t know which part of the code deserves attention. In a large codebase, the number of possible focus points is massive, which means the model can easily get distracted and look in the wrong place.

The WHAT problem is that even if the model examines the correct location, it still needs to guess what kind of bug it should be looking for, such as memory issues, race conditions, or API misuse. Without guidance, it may pick the wrong category entirely and increase the chances of missing the real bug.

Let’s explore how Google and OpenAI approached the challenge.

Google’s Deep Sleep attempted to address these issues by analyzing code changes, such as git diffs or commit patches, linked to known CVEs, and verifying whether the fix or nearby code contains similar problems.

Figure 1: Google’s blog on how Deep Sleep works

It’s a good approach and handles both the WHERE and WHAT problems reasonably well. However, without a constant supply of new vulnerabilities discovered by researchers, along with their corresponding patches, it risks running out of material to analyze.

OpenAI took a different path by focusing on new commits.

Figure 2: OpenAI blog on how Aardvark works

They claim that around 1.2% of commits introduce known security issues, and their goal is to identify and address these. This helps address the WHERE problem by narrowing focus to potentially dangerous commits, but it doesn’t fully tackle the WHAT problem, since the model still has to decide what kind of bug to look for in each case.

Our approach: Combining static analysis with LLMs

Our approach to solving the WHERE and WHAT problems involves combining static analysis tools with an LLM.

However, before we attempt to understand our approach, let’s first understand what static analysis is.

Static analysis is the process of parsing source code statically, without executing it, to identify security bugs. It does so by extracting variables, structures, and code relationships. Save them into a database and build code-flow and data-flow graphs. Those graphs can then be checked against predefined rules or queries. For example, a rule might flag any use of memcpy where the source size isn’t properly bounded by the destination, something that could lead to memory corruption, unsafe flows, and other critical issues.

One of the most popular tools in this space is CodeQL, which is owned by GitHub and is integrated into GitHub Actions, allowing developers to scan their code upon build during the CI/CD. It supports a wide range of languages, including C/C++, C#, Java, JavaScript, TypeScript, Python, Go, Ruby, Swift, and Kotlin. You can run it manually through the CLI or via a VS Code extension.

CodeQL analysis is based on queries, divided into stable and experimental sets. The stable ones will have a lower percentage of false positives.

import cpp from BlockStmt blk where blk.getNumStmt() = 0 select blk

Snippet 1: Simple CodeQL query that selects all empty blocks in the code

At this point, you might challenge our approach:

If static analysis tools are so powerful, why bother combining them with LLM?

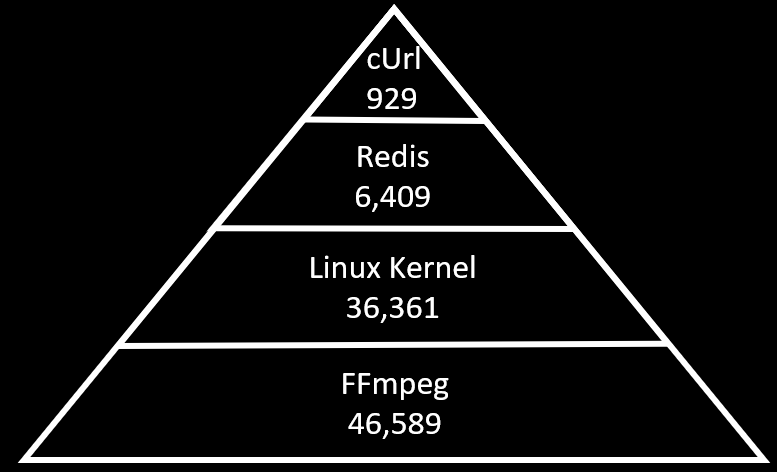

To answer that, we tried running CodeQL on a few repositories ourselves. We selected specific queries that, in our opinion, will be critical in the event of real issues. The result?

A massive flood of results.

Figure 3: The number of CodeQL results on each repository

There are potentially numerous security vulnerabilities that, if reviewed manually, require an average of three minutes per issue, resulting in a single researcher needing more than two years to complete the task. And that’s assuming we work on it as our full-time job, every single day. Meanwhile, new code is written, new queries are added, and if we switch to a new static analysis tool, we have to review thousands of fresh alerts all over again.

This makes static analysis tools less effective for tackling real bugs, as the work accumulates, and the likelihood of finding bugs is relatively low.

But ignoring those alerts can leave real vulnerabilities in the codebase, waiting for a patient attacker to discover.

The false-positive reality

You might wonder how many of those findings are real issues and how many are noise. Honestly, it’s hard to know without spending years reviewing everything. False vary significantly between queries, and there is little research in academia or by security researchers specifically on CodeQL.

However, there is extensive research on static analysis tools in general. In one study, developers were asked to test different static analysis tools, and these were some of the quotes:

“In one tool we use, about 80% of findings are false positives; only ~20% lead to fixes, and even those are rarely serious.”

“We wouldn’t mind wading through 100 false positives if we thought there were actually going to be genuine issues there… we went back to manual reviews.”

Static analysis is robust, but the signal-to-noise ratio can be brutal. And that’s precisely why static analysis alone can be challenging at scale, and why combining it with LLMs might even be necessary.

Putting the thesis to the test

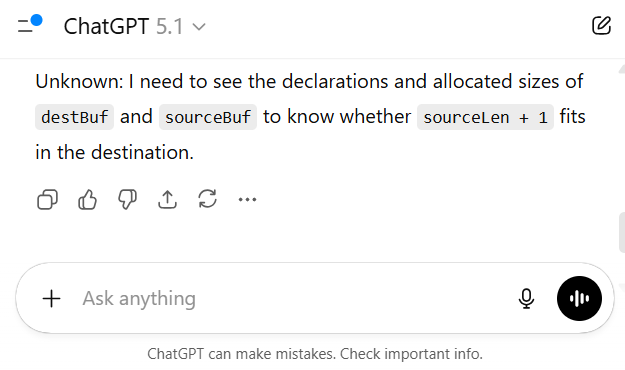

Our thesis on using CodeQL with LLM is straightforward: we take the source code, generate a CodeQL database of it, run CodeQL queries on the database, and then pass every alert from the results to the LLM to determine whether each one is a genuine issue or a false positive.

Figure 4: This is what combining CodeQL with LLM will look like

To test our thesis, let’s start with a simple C code that performs a memcpy operation.

#include

#include

#include

#define DEST_SIZE 16

size_t read_input(char** sourceBuf) {

char* buf = malloc(DEST_SIZE + 1);

size_t bufSize = 0;

int c;

while (bufSize < DEST_SIZE) {

c = getchar();

if (c == EOF || c == '\n') {

break;

}

buf[bufSize++] = (char)c;

}

buf[bufSize] = '\0';

*sourceBuf = buf;

return bufSize;

}

int main(void) {

char destBuf[DEST_SIZE + 1];

char* sourceBuf;

size_t sourceLen;

sourceLen = read_input(&sourceBuf);

if (sourceLen <= 0) {

return 1;

}

memcpy(destBuf, sourceBuf, sourceLen + 1);

printf("%s\n", destBuf);

free(sourceBuf);

return 0;

}

Snippet 2: false positive example

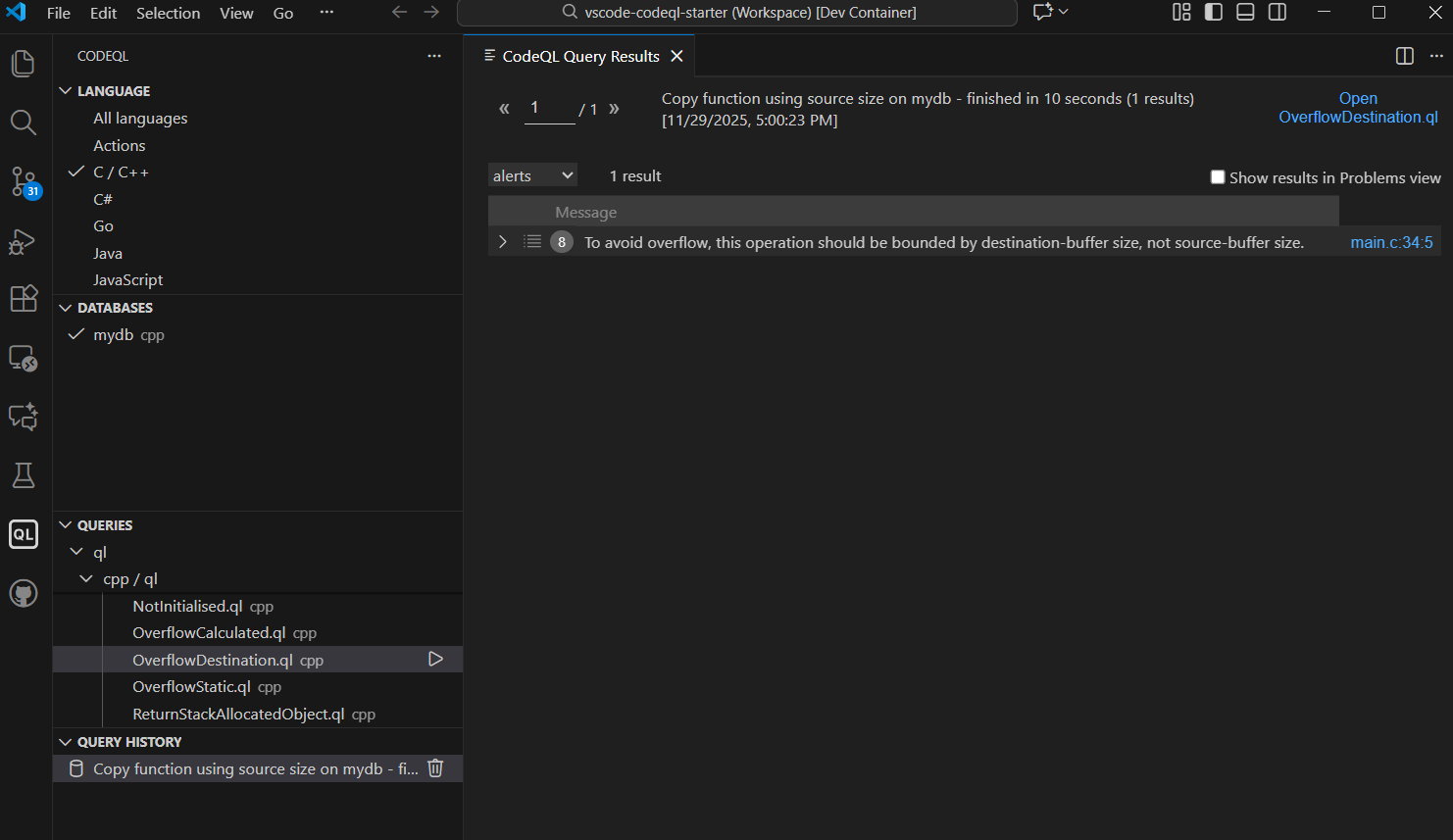

When we run CodeQL on this code, it yields this one security issue:

Copy function using source size.

However, upon examining the code, it becomes clear that this isn’t the case, and we don’t have a vulnerability here. Both source size and destination size can’t be bigger than the DESTINATION_SIZE macro, so the source size can never exceed the destination size. We have a classic false positive here.

Now, if we examine the output from CodeQL, we see that it simply displays a message and a line number.

Figure 5: Running CodeQL in VS Code

If we simply copy-paste the result from CodeQL into an LLM and ask whether it’s a real issue, of course, it won’t work. A line number by itself gives the LLM zero context.

But what if we provide the line of code where the issue exists?

Is that enough?

Let’s test it.

What happens when the LLM gets too little context

Using the ChatGPT Personalization feature, we added the following prompt as Custom Instructions.

You are a security static-analysis assistant. You are given: - Metadata about a CodeQL alert. - A snippet of C source code that may contain the reported problem. Your job: - Decide whether the alert is likely a real bug, given ONLY the code shown. - Respond VERY BRIEFLY (at most 2 sentences). Rules: - If you can determine it IS a real bug, start with: "Bug:" and give a short reason. - If you can determine it is NOT a real bug, start with: "Not a bug:" and give a short reason. - If you CANNOT TELL from the snippet and you need more code, start with: "Unknown:" and state EXACTLY what additional code or context you would need. Do not speculate beyond the shown code. Do NOT call something a bug unless the code shown is clearly unsafe. Always list concrete missing pieces when you answer "Unknown:".

Snippet 3: Custom instructions for ChatGPT to act as a security assistant

Then we generated a prompt to be used in ChatGPT-5.1 to test if it works. You can see that the message is directly built from the VS Code CodeQL extension results:

Static analysis finding: Name: Copy function using source size Message: To avoid overflow, this operation should be bounded by destination-buffer size, not source-buffer size. Location: look at main.c:36 with 'memcpy' Here is the relevant code with full context: ```c memcpy(destBuf, sourceBuf, sourceLen + 1);

Snippet 4: Prompt to query the LLM if this is a real issue, given only one line

Let’s see how the LLM responded:

Figure 6: ChatGPT response to only one line of code

Not surprisingly, the LLM said it needed more context.

So the interesting question is: how much more? And how much is enough?

From the CodeQL results (Figure 5), we only know the line number where the issue occurs. How can we derive more context from that line number? Let’s send additional lines of code before and after, say four lines before and four lines below.

Let’s try.

Static analysis finding:

Name: Copy function using source size

Message: To avoid overflow, this operation should be bounded by destination-buffer size, not source-buffer size.

Location: look at main.c:36 with 'memcpy'

Here is the relevant code with full context:

```c

sourceLen = read_input(&sourceBuf);

if (sourceLen <= 0) {

return 1;

}

memcpy(destBuf, sourceBuf, sourceLen + 1);

printf("%s\n", destBuf);

free(sourceBuf);

Snippet 5: Prompt to query the LLM if this is a real issue, given four lines before and after

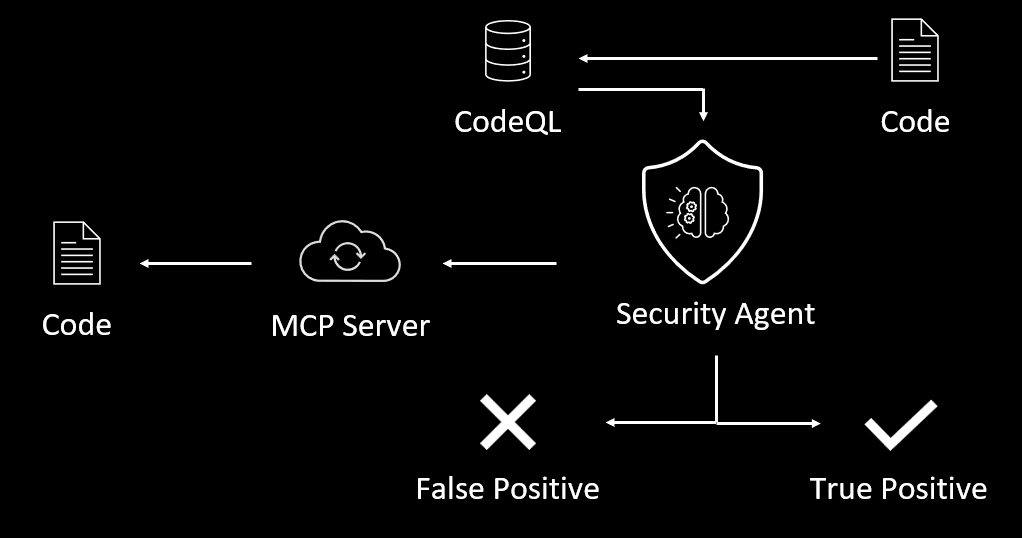

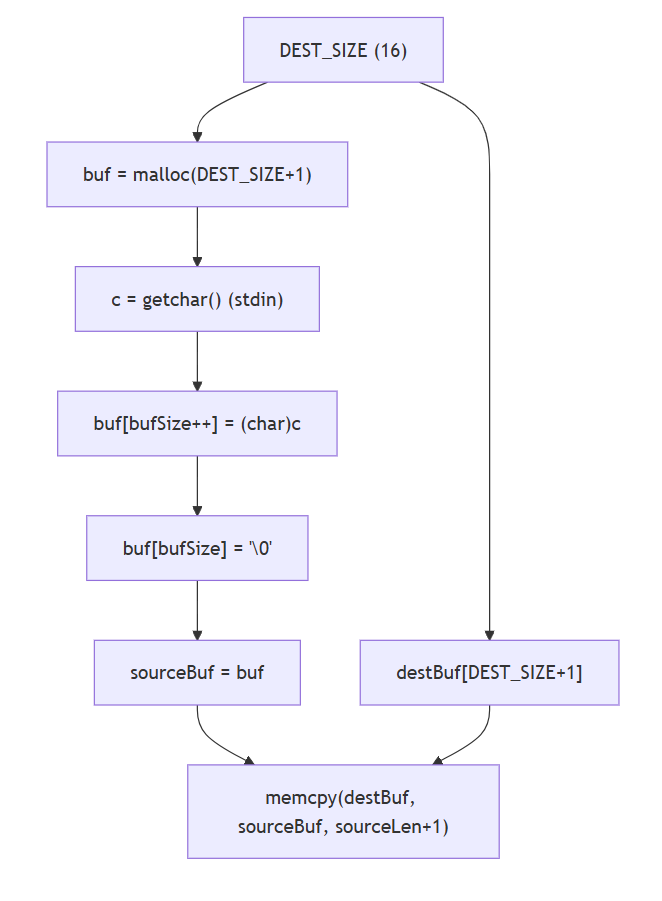

Figure 7: ChatGPT response to a few lines of code

As you can see, this is still not enough for the LLM to determine anything reliably.

So now what? We have yet to answer these questions: How do we know when the LLM has enough context? Do we need the entire file? Multiple files? Or just the full function? All of these questions are valid, and they led us to consider a different angle.

Letting the LLM ask for its own context

Our hypothesis was: Let’s use the LLM to determine what context it needs.

- We start by providing the issue found by CodeQL with the full function where the issue exists.

- We ask the LLM which other context it needs.

- If the LLM asks for more, we provide it on demand

Figure 8: The flow with context on demand

Sounds great in theory, but before we even test that theory, can we even extract the function when we only have the output line number?

It turns out that it’s not trivial, especially in C

The complex problem of extracting functions in C

We thought of using regex or counting brackets, but then we remembered a classic StackOverflow answer:

“You can’t parse C code with regex.”

We either need a compiler or implement a complex parser.

For example, consider this C code:

#define BEGIN {

#define END }

int log_and_add(int x, int y)

BEGIN

printf("adding {x,y} = %d\n", x + y); // brace chars inside string

#ifdef DEBUG

/* Fake function in a comment:

int fake(int z) { return z*z; }

*/

#endif

int (*callback)(int); // looks like a function, but it's a pointer

return x + y;

END

Snippet 6: It would be hard to parse this code with regex or bracket count. This code is based on a Stack Overflow answer about parsing C functions with regex

Here we have:

- Macros that are in brackets

- Brackets inside strings

- Function call inside a comment

- Pointers that resemble function calls

Parsing this correctly is… not fun.

Why code indexers didn’t work

By now, we thought we might be able to utilize a code indexer like Elixir.

Indexers work similarly to static analysis: they traverse the codebase and record all types, functions, variables, and other entities. They’re super valuable for giant projects like the Linux Kernel.

This is how you can run Elixir in order to index the Matter library (connecthomeip):

docker exec -it -e PYTHONUNBUFFERED=1 elixir-container /usr/local/elixir/utils/index-repository connectedhomeip https://github.com/project-chip/connectedhomeip

Snippet 7: Example command for running Elixir’s index-repository utility in Docker, targeting the Matter (connectedhomeip) repository. See Elixir GitHub repository for details.

But we ran into two huge problems:

- It took over 10 hours to index the repository.

Imagine scaling that to large projects. - Elixir requires a GitHub URL, but the correct way to clone this repository is with the —recursive option, which pulls in all third-party dependencies. Elixir doesn’t support this, so you end up missing the code you depend on.

git clone --recurse-submodules [email protected]:project-chip/connectedhomeip.git

Snippet 8: The correct way to clone the Matter repository

So, code indexers were out.

Using CodeQL as a code navigator

Then we realized that if code indexers basically do the same job of static analysis, and we are already using static analysis (CodeQL),

Why not use the CodeQL database itself to extract all the necessary context on demand?

So, the idea became:

- Run one CodeQL query to get the function whose start line is smaller than the issue line, and the end line is bigger than the issue line

- If the LLM requests additional context, run another query and extract the necessary context.

Figure 9: The flow with context on demand using CodeQL queries

In theory, it can work really well:

CodeQL databases are generated during compile time, meaning:

- They include all third-party code

- They’re already available via GitHub API (CI/CD).

- No need to clone the repo

- Querying them gives you precise, compiler-level structure.

The performance bottleneck

Well… almost perfect.

When we executed these context queries, we discovered that CodeQL queries take about 2.5 minutes on average for each query, since dynamic queries require CodeQL to resolve all types, references, and scopes on the fly.

Precompiled queries take around 40 seconds, but to provide the LLM with an on-demand context, we need the query to be dynamic, which translates to an average of minutes.

To put this in perspective:

When you run CodeQL on FFmpeg alone, you will get 46,589 potential issues.

46,589 × 2.5 minutes = 116472.5 minutes (almost 11 months)

That’s a lot of time!

So, we needed a better solution.

Solution: Pre-Extracting functions into a CSV

Then we figured that instead of running every query each time the LLM requests it, we should take a cleaner approach:

Write one CodeQL query that selects every function in the database (including the caller function) and dumps it into a CSV file.

Yes, the CSV file can be massive, but time is our limitation, not space.

Then the workflow becomes:

- Extract all function information to CSV

- Run CodeQL on the code and save all the issues.

- Get the line where each issue occurs

- Scan the CSV to find the function :

function_start_line <= issue_line <= function_end_line - Extract that function directly from the code using the information from the CSV.

- If the LLM requires the caller function, simply search for its ID in the same context and send the updated context to the LLM.

Even better, we can save even more time because every CodeQL database includes a src.zip file containing all the source code used to build the database.

There is no need to clone the repository; simply download the database once from the GitHub API.

Figure 10: The flow of context on demand using CSV files

We repeated this process for structs, globals, macros, and other types.

import cpp

from GlobalOrNamespaceVariable g

select g.getName() as global_var_name,

g.getLocation().getFile() as file,

g.getLocation().getStartLine() as start_line,

g.getLocation().getEndLine() as end_line

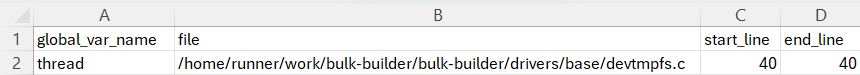

Snippet 9: Example of CodeQL query to select all Global Variables

Figure 11: The CSV file output

You are probably asking yourself, What about the performance?

About 3 seconds on average to find any other function in the CSV.

We now have an effective code navigator that can provide the LLM with the exact context it needs.

Testing LLM with full context

Now that we have a reasonably sophisticated AI Agent that can provide the LLM with all the necessary context, everything should work well.

Let’s test it.

We’ll give the LLM the same prompt as before, but this time with the entire context the LLM needs, and see how it responds. Our goal is simple: the LLM should say this is a false positive, because the source buffer can never be larger than the destination.

Static analysis finding:

Name: Copy function using source size

Message: To avoid overflow, this operation should be bounded by destination-buffer size, not source-buffer size.

Location: look at main.c:36 with 'memcpy'

Here is the relevant code with full context:

```c

#include

#include

#include

#define DEST_SIZE 16

size_t read_input(char** sourceBuf) {

char* buf = malloc(DEST_SIZE + 1);

size_t bufSize = 0;

int c;

while (bufSize < DEST_SIZE) {

c = getchar();

if (c == EOF || c == '\n') {

break;

}

buf[bufSize++] = (char)c;

}

buf[bufSize] = '\0';

*sourceBuf = buf;

return bufSize;

}

int main(void) {

char destBuf[DEST_SIZE + 1];

char* sourceBuf;

size_t sourceLen;

sourceLen = read_input(&sourceBuf);

if (sourceLen <= 0) {

return 1;

}

memcpy(destBuf, sourceBuf, sourceLen + 1);

printf("%s\n", destBuf);

free(sourceBuf);

return 0;

}

Snippet 10: Prompt to query the LLM if this is a real issue, given the entire context

Figure 12: ChatGPT response when given the entire context

And… the LLM got it wrong.

The LLM says that the code has a memcpy using source size problem. Even though that’s technically true, any human looking at this code would immediately realize it’s not actually a security issue. So why didn’t the LLM reach the same conclusion?

Why the LLM failed

Hint: It’s always the prompt – aka “What (and how!) are you actually asking?” After looking carefully at the prompt, we noticed the problem:

The prompt and CodeQL are too focused on confirming whether the pattern memcpy using source size exists.

For that specific question, the correct answer is “yes.”

But the real question should be:

Is this pattern really exploitable? To answer that, we need to examine other parts of the code, understand the data flow, and verify whether the source can ever exceed the destination. The LLM wasn’t instructed to do that.

We could modify the prompt and force the LLM to check whether the destination size is smaller than the source, but that would be a trap. Complex code can hide size changes and indirect assignments, and if we start adding specific instructions, we’ll eventually overfit the prompt and miss edge cases.

At this point, we realized something important:

An LLM can review the code, but it’s akin to having a junior security researcher. We want it to think like an experienced researcher.

Figure 13: The way an experienced researcher sees the code

When an experienced researcher reviews the code, he would probably have this flow in mind:

- Examine data flow

- Examine control flow

- Identify the sources of variables and how they change over time.

That prompted us to consider a better way to build the prompt for the LLM by translating the thought process of experienced researchers, who will look for flows and variable sources. And will test assumptions step by step.

Guiding the LLM with high-level questions

Instead of providing the LLM just the issue, we can ask it “Guided Questions” before making a judgment to enhance the LLM’s reasoning process. For example:

- Where is the source buffer declared?

- What size does it have?

- Does this size ever change?

- Where is the destination buffer declared?

- Are these buffers assigned from another location?

- What conditions or operations affect them?

Static analysis finding:

Name: Copy function using source size

Message: To avoid overflow, this operation should be bounded by destination-buffer size, not source-buffer size.

Location: look at main.c:36 with 'memcpy'

Here is the relevant code with full context:

```c

#include

#include

#include

#define DEST_SIZE 16

size_t read_input(char** sourceBuf) {

char* buf = malloc(DEST_SIZE + 1);

size_t bufSize = 0;

int c;

while (bufSize < DEST_SIZE) {

c = getchar();

if (c == EOF || c == '\n') {

break;

}

buf[bufSize++] = (char)c;

}

buf[bufSize] = '\0';

*sourceBuf = buf;

return bufSize;

}

int main(void) {

char destBuf[DEST_SIZE + 1];

char* sourceBuf;

size_t sourceLen;

sourceLen = read_input(&sourceBuf);

if (sourceLen <= 0) {

return 1;

}

memcpy(destBuf, sourceBuf, sourceLen + 1);

printf("%s\n", destBuf);

free(sourceBuf);

return 0;

}

Before deciding if the issue is real, you *MUST* answer first on the questions regarding the source and destination variables.

1. Where are they declared, what are their sizes, and do those sizes ever change?

2. If they take values from other variables, where are those variables declared and what sizes do they have?

3. Are there any checks or constraints on the source, the destination, or the variables assigned to them?

4. What other operations act on these variables?

Snippet 11: guided questions for memcpy using source size

As you can see, this prompt doesn’t contain any other information about the issue from asking the LLM to describe the flow.

Let’s use this prompt while examining the same simple C code from before.

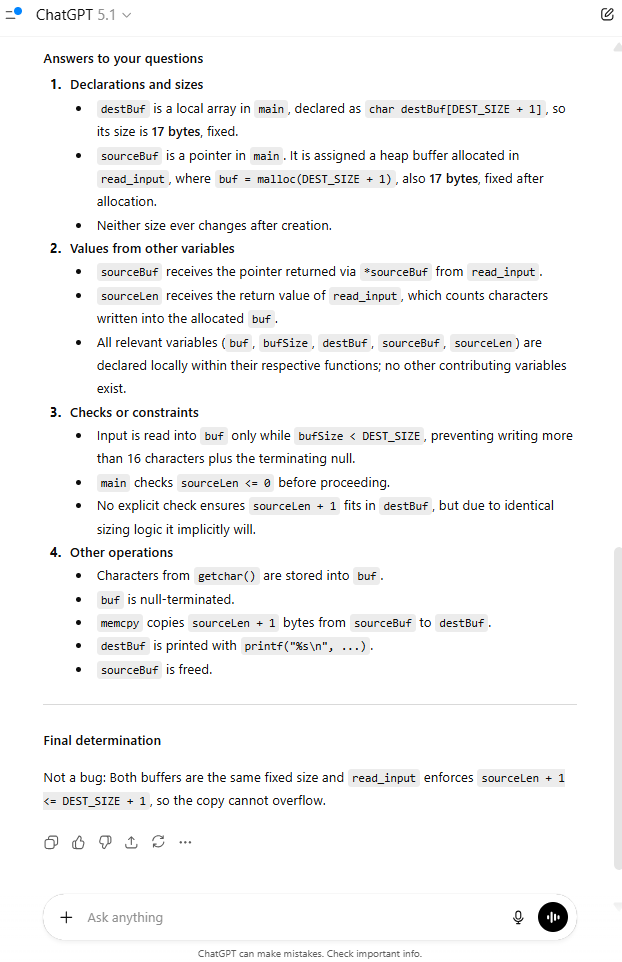

Figure 14: ChatGPT response when given the entire context and with Guided questions

Yes! It worked!

The LLM correctly recognized it as a false positive.

Why does this work?

Because the LLM generates its output based on the previous text, this format encourages it to reason step-by-step. By answering focused questions about variables and flows, the model simulates the reasoning of a senior researcher, and the final decision is made with all the correct information fresh in context.

And since the LLM now “talks through” the variables, sizes, assignments, and paths, it naturally avoids the earlier mistake, requiring no special-case instructions, just like a senior researcher.

But it’s important to remember that different types of issues require different guided questions. For some vulnerabilities, the LLM needs to reason about control flow. For others, it must analyze variable types, and in some cases, it has to focus on special conditions or edge cases.

The key is to consider how you would explain the issue to a junior security researcher, what you would advise them to look for, and how you would phrase it so they understand the core idea. Those same explanations should become the questions you ask the LLM.

Once you craft strong, well-focused questions, they will reliably work for all issues of the same type.

Running the method in the real world

At this point, we have:

- A practical answer to the WHERE and WHAT problems in static analysis

- An AI agent that extracts all necessary context directly from the CodeQL CSV output

- A reliable method to guide the LLM toward evaluating actual vulnerability, rather than matching surface-level patterns

We ran the tool across 100 large open-sourced GitHub repositories, selected by star count in C language, and scanned for multiple different issue types.

For each issue category, we designed specific guided questions to focus the LLM on the exact semantics and context required for an accurate judgment of exploitability.

The table below presents the aggregated results across all CodeQL queries included in the experiment.

We report:

- Total findings generated by CodeQL

- Remaining findings after AI filtering

- False-positive reduction rate

- Confirmed real issues

- How many of the “real” issues were actually exploitable or meaningful

Important:

A “real” issue does not automatically imply a CVE-worthy or practically exploitable vulnerability.

Even when the code pattern is correct, the function may be:

- never called anywhere,

- used only in tests or example snippets,

- part of a non-security-critical component, or

- hosted in a repository that explicitly warns it is not secure or not intended for production.

Therefore, “real” means only “not a false positive,” not necessarily that the issue is exploitable in practice.

CodeQL findings

| Rule Name | Total Findings | Findings After Filtering | False Positive Reduction (%) | Confirmed Real Issues | Real Issues (% of Remaining) | Associated CVEs |

| Copy function using source size | 189 | 16 | 91.53% | 2 | 12.50% | Redis, Libretro |

| Dangerous use of transformation after operation | 99 | 11 | 88.89% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Incorrect return-value check for scanf-like function | 52 | 19 | 63.46% | 1 | 5.26% | FFmpeg |

| Missing return-value check for a ‘scanf’-like function | 549 | 162 | 70.49% | 101 | 62.35% | RetroArch |

| new[] array freed with delete | 6 | 1 | 83.33% | 1 | 100.00% | |

| Not enough memory allocated for array of pointer type | 31 | 8 | 74.19% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Operator precedence logic error | 25 | 1 | 96.00% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Pointer offset used before check | 547 | 44 | 91.96% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Pointer to stack object used as return value | 132 | 7 | 94.70% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Potential double free | 70 | 5 | 92.86% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Potential use after free | 302 | 7 | 97.68% | 2 | 28.57% | |

| Redundant/missing null check of parameter | 242 | 26 | 89.26% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Scanf function without specified length | 84 | 42 | 50.00% | 35 | 83.33% | Linux Kernel, bullet3, Libretro |

| Unchecked return value used as offset | 324 | 93 | 71.30% | 2 | 2.15% |

Introducing Vulnhalla

Using this method, we built an open-source tool called Vulnhalla. It allows you to download a CodeQL database directly from GitHub, run queries on it, and feed the results into an LLM. For each finding, the tool automatically retrieves the relevant code context and applies issue-specific guided questions. This enables the model to reason more accurately about the underlying logic, filter out false positives, and surface only the findings with real potential.

Vulnhalla addresses the persistent signal-to-noise bottleneck in large-scale static analysis by combining CodeQL with LLM-powered reasoning for precise and scalable vulnerability discovery.

The tool currently supports full code navigation for C and C++ and includes several example templates for guided questions. We invite the community to contribute by expanding support to additional programming languages. This involves writing CodeQL queries that extract the relevant data into CSV form based on language semantics, and creating new guided-question templates tailored to each issue type and language.

Key Takeaways and Next Steps for CodeQL and LLM Vulnerability Hunting

Our key findings and technical contributions for the research community are:

- Up to 96% false positive reduction: In our experiments, we observed up to 96% reduction in false positives for specific issue types, which significantly alleviates the manual review burden of static analysis at scale. This reduction will vary depending on the specific issues and Guided Questions.

- Performance optimization: Eliminated multi-minute context retrieval latency by pre-indexing CodeQL database entities (functions, structs) into a quickly queryable CSV format. This allows the LLM agent to fetch comprehensive context in approximately 3 seconds per query.

- Enhanced LLM reasoning: We utilized a Guided Question prompting strategy to compel structured LLM reasoning. This technique employs a multi-step analysis: tracing data flow and control flow, which emulates the analysis of experienced researchers, shifting the focus from pattern-matching to assessing real

- Proven impact: The methodology was validated by directly leading to the discovery of multiple verified vulnerabilities (all of which were handled through responsible disclosure).

This validated hybrid approach demonstrates a promising step for AI-based automated vulnerability discovery. By increasing the efficiency and accuracy of identifying high-impact flaws, we believe this work can help significantly close existing security gaps. We are releasing the Vulnhalla tool as an open source to encourage further refinement and research.

https://github.com/cyberark/Vulnhalla

Simcha Kosman is a senior cyber researcher at CyberArk Labs.